I don’t often review nonfiction. But I thought it was worth it for this book, which could be relevant and helpful to a lot of teen girls (and adult women, for that matter) like me. I’ve never been diagnosed with Asperger’s*, but reading this makes it pretty clear that I’d qualify. In the past when I’ve looked at the symptoms lists, it didn’t ring true—but that’s because (like most everything in the medical community) they focus on how the condition presents in boys and men (you know, the default human).

Simone’s book is comprised primarily of personal anecdotes from her and other girls/women with Asperger’s and her commentary on the significance of those. She also gives out quite a bit of advice. Near the end, the book started feeling a little pseudo-sciency to me, particularly when she gets into some of the stomach issues and how to deal with them, because she doesn’t do a thorough scientific analysis of it. This isn’t really meant as a criticism of the book as a whole; I just found that I didn’t put as much trust in that part (I am just very cynical when it comes to anyone recommending a certain diet).

Since this is nonfiction, I’m going to go through the chapters and comment on each a little instead of giving a more general picture. Each chapter contains Simone’s anecdotes and commentary followed by Advice to Aspergirls and then Advice to Parents. For the purposes of clarity, I’ll use AS for Asperger’s syndrome and NT for neuro-typical, as Simone does.

1. Imagination, Self-Taught Reading and Savant Skills, and Unusual Interests: Simone talks about how people with AS love information probably because it anchors our thoughts. A lot of AS girls teach themselves specific skills, even reading, and may have unusual abilities in certain areas (though this isn’t that common and it isn’t uncommon for AS girls to have learning disabilities, too). One thing that was particularly interesting to me is that autistic kids have been found to have higher fluid intelligence but not necessarily higher crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence is the ability to see relationships between things that aren’t obviously related. I do this all the time, sometimes confusing people with my connections. Crystallized intelligence is more traditional intelligence—the ability to learn stuff and use it. One really interesting point was that while many AS girls develop obsessive interests just like AS boys do, they tend to be in the domain of more acceptable things (books, art, music, animals, etc.)—all of which are “normal” for many girls. She says we “want to fill our minds with knowledge the way others want to fill their bellies with food” (p. 23). As someone working on her fifth degree with plans for a sixth, I can certainly relate to that.

2. Why Smart Girls Sometimes Hate School: In a word, bullying. It is true that AS girls don’t have the social skills of NT girls. But even outside of that, most AS girls actually don’t love school despite having a love of knowledge. It’s too structured and doesn’t let us focus on the areas that interest us. Simon says that “Aspergirls do not thrive under scrutiny if it has the slightest bit of hostility in it” (p. 31). I can relate to this very well. I wither when people judge me, which I hate but I’ve never been able to get past this tendency.

3. Sensory Overload: Simone points out that it’s not really true that AS people feel less, as was previously though, but that instead we feel things much more intensely. This is where sensory overload comes in. As people are often deeply disturbed by things other people don’t even notice. I know that the more people I’m around, the more uncomfortable I get—especially as the noise level increases. I hate sudden loud noises like balloons popping. Though I think I’m lucky because I don’t have too many sensory issues. A lot of AS people can be bothered by many sounds, sights, and even tactile sensations.

4. Stimming, and What We Do When We’re Happy: I only heard of swimming fairly recently. It’s short for self-stimulatory behavior. This covers things like rocking, clapping, twirling, and hand flapping, all things AS people can do when they’re overwhelmed (and sometimes when they’re happy, too). I’m a chronic pen twirler. Not sure if it’s stimming or if it’s just a thing I do to help me think (I swear I think better with a pen in my hand).

5. On Blame and Internalizing Guilt: We all know that boys and men rarely question themselves or blame themselves or internalize much of anything (other than “emotions other than anger are bad,” of course). This is one significant way AS girls are different from boys, because we do blame ourselves for our ”weird” behavior that we can’t control and subsequently start feeling guilty about it. But even more importantly, this blame often comes from external sources, when people think AS girls are behaving that way on purpose.

6. Gender Roles and Identity: This was one of the most interesting chapters to me because Simone says that most AS girls don’t get gender roles and often shirk them. This is partially because we like to wear comfortable clothes (sometimes due to the skin sensitivity some of us have). But this also extends to identity in general, with a lot of AS girls being rather chameleon-like. Some simply don’t have much of a sense of self. I can certainly relate to this as I despise the expectations people have based on gender. It has always driven me crazy that while it’s fine to recognize there are differences between men and women, generalizations don’t apply in every single case.

7. Puberty and Mutism: This chapter touched on puberty, but was mostly about mutism. Mutism is the situation where an AS girl is simply unable to speak and often even think. I’ve been there before. It’s bizarre and frustrating.

8. Attraction, Dating, Sex, and Relationships: I skimmed this chapter, but one thing I did get out of it was that while a lot of AS girls aren’t remotely interested in romance, others are. Those who are are prone to becoming obsessed with the object of interest and coming across as stalker-y. Another point is that because we don’t experience romance in the same way, many of us marry early or because it’s “time” rather than because there’s a real connection with the partner. Breakups are often worse for AS girls because of the break to a routine.

9. Friendships and Socializing: It’s true that AS people tend to lack social skills, so common socializing is very difficult. But it also means that it’s hard to maintain friendships in general.

10. Higher Learning: College is kind of a mixed bag. Some AS women do really well because of the routines, focus required, and opportunities for learning, but most others struggle with sensory overload and managing all the aspects of college life. Simone talks about the importance of trying to get assistance from the school (such as through the Office of Disability Services) if necessary, but also that many of the support services are very lacking and the people are often uninformed.

11. Employment and Career: Simone says that a lot of AS women struggle in this area because of lack of education or qualifications. Additionally, getting jobs in the first place can be difficult due to the social skills problems. She emphasizes the importance of AS women trying to establish themselves in good jobs, especially since many stay single and can’t rely on someone else to support them.

12. Marriage and Cohabitation: I also skimmed this chapter because it isn’t relevant to me.

13. Having Children: Ditto.

14. Ritual and Routine, Logical and Literal Thinking, Bluntness, Empathy, and Being Misunderstood: Routine and even rituals are a way for AS girls to control the world around them as much as possible. Simone also talks about how literal thinking can sometimes make problems for us. I know for me that when I read, I’m very literal. Symbolism usually goes flying over my head and I cannot enjoy poetry. Bluntness is another area that can be a challenge. Simone points out that AS girls often feel misunderstood because whatever we said bluntly or understood literally was not intended to have the impact it did on the other person.

15. Diagnosis, Misdiagnosis and Medication: A lot of AS women have never been diagnosed because the medical community is slightly clueless about AS in women, as opposed to men. Many AS women have been diagnosed with various mental illnesses and often prescribed medications based on that, when it completely misses the mark. Many women don’t find out they have it until their child is diagnosed.

16. Depression Meltdowns, PTSD, and More about Meds: Apparently “meltdowns” are a common occurrence in people with AS. This chapter talks about depression ones. These are extreme depressions that take over an AS person’s life temporarily and can be caused by a variety of things. Simone does address the fact that AS people are prone to depression that can be treated by meds.

17. Temper Meltdowns: This chapter is basically about the temper tantrums that AS people sometimes have. They can be triggered by almost any sensory overload and can manifest in many different ways. AS women are more prone to crying than men, but the meltdowns can be violent or just excessively phrased or acted out. However they occur, they are usually embarrassing after the fact and women especially are considered crazy, whereas men are more often forgiven. I can relate to this one, too, as (especially when I was younger), I would be triggered by something and be instantaneously overcome with this intense rage. I never was violent toward other people, but I destroyed plenty of my own things and also would say horrible things to people. All very humiliating.

18. Burning Bridges: When you say horrible things to people, they don’t want to be around you. As mentioned earlier, a lot of AS women have trouble keeping relationships up and this can be extended to not just keeping them up but ruining them. But Simone also talks about how AS women “start over” repeatedly. Cut off all ties with the old life and start afresh. I can also relate to this one—over and over while I was in college I would decide it was time for a change and I would move, change jobs, and either go back to college or drop out of it.

19. Stomach Issues and Autism: Apparently some people think that autism in general is caused by stomach problems during early formative months. There are also several diets that are supposed to help with autism. I’m a skeptic.

20. Getting Older on the Spectrum: Simone talks about how most AS women stay single so money can be a challenge. So can loneliness and health problems. But otherwise, most stop caring as much about what people think of their unusual behaviors. But also, in some ways, older women are allowed to be more eccentric.

21. On Whether Asperger Syndrome is a Disability or a Gift and Advice from Aspergirls to Aspergirls: I didn’t read this one because Simone started off by saying she preferred the term “differently-abled” over “disabled,” which I can’t stand. This seems to me like a term that non-disabled people have come up with to try to make disabled people feel better about themselves. I find this insulting. I mean, you should own it.

22. Give Your Aspergirl some BALLS: Belief, Acceptance, Love, Like, and Support: I didn’t read this one either.

23. Thoughts and Advice from Parents of Aspergirls: Or this one.

There are also a couple of appendices which listed the symptoms of female AS and then the main differences between male and female AS. These are good.

* Yes, I know it’s not technically a diagnosis anymore, but I think it is a different enough thing from more challenging cases of autism spectrum disorder, so it’s a valuable distinction. And people have a sense for what you’re talking about, even if they don’t get it exactly right.

This is a really interesting and unique book. It’s steeped in Mexican-America culture, but not really in a positive way—the main character, Julia, basically hates every aspect of it. To me this was interesting because one of the reasons she hates it is that she can’t navigate it well—she’s socially awkward, but not in the “standard” way (at least this was my take on it). No, she says and does the wrong thing for her culture, which might be okay in white American culture (though definitely not always).

This is a really interesting and unique book. It’s steeped in Mexican-America culture, but not really in a positive way—the main character, Julia, basically hates every aspect of it. To me this was interesting because one of the reasons she hates it is that she can’t navigate it well—she’s socially awkward, but not in the “standard” way (at least this was my take on it). No, she says and does the wrong thing for her culture, which might be okay in white American culture (though definitely not always). This book is a collection of short stories set in various points of US history ranging from 1838 to 1984. The stories are all about girls bucking the system in some way, but those ways vary widely over the book. The stories are all realistic except for a couple that have some magical realism elements. The stories also run the gamut on the diversity spectrum, including girls of several different religions, several protagonists of color (and different ethnicities, too), at least one lesbian, one character in a wheelchair, and another on the autism spectrum.

This book is a collection of short stories set in various points of US history ranging from 1838 to 1984. The stories are all about girls bucking the system in some way, but those ways vary widely over the book. The stories are all realistic except for a couple that have some magical realism elements. The stories also run the gamut on the diversity spectrum, including girls of several different religions, several protagonists of color (and different ethnicities, too), at least one lesbian, one character in a wheelchair, and another on the autism spectrum. Darius the Great Is Not Okay is a unique book. Darius is an American kid whose mother is from Iran and whose father is Teutonic stock, and he is under treatment for depression. You don’t see a lot of YA featuring boys of color with depression, so I was curious to see how this one would play out. Also, most of the book is set in Iran, which is cool—I’ve only personally encountered one other YA book set there (not that I’ve looked extensively, but still).

Darius the Great Is Not Okay is a unique book. Darius is an American kid whose mother is from Iran and whose father is Teutonic stock, and he is under treatment for depression. You don’t see a lot of YA featuring boys of color with depression, so I was curious to see how this one would play out. Also, most of the book is set in Iran, which is cool—I’ve only personally encountered one other YA book set there (not that I’ve looked extensively, but still). Juliet Takes a

Juliet Takes a

First, I have to say that Dramarama plays heavily with stereotypes—namely Gay Best Friend and Theatre Geek. However, it’s not a bad thing at all because Lockhart brings both to life so effectively.

First, I have to say that Dramarama plays heavily with stereotypes—namely Gay Best Friend and Theatre Geek. However, it’s not a bad thing at all because Lockhart brings both to life so effectively. Girl Mans Up is one of the best books I’ve read in a while. This is the first gender nonconforming girl I’ve really seen in a book (I’m sure there are others, but I haven’t encountered them) and I was really excited to read Pen’s story. It reminded me in some ways of what I’m trying to do with my own book Ugly, even though Pen is different in a lot of significant ways from my protagonist.

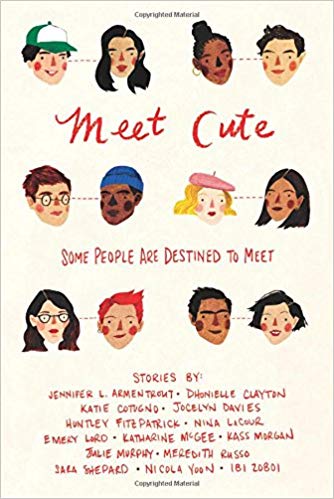

Girl Mans Up is one of the best books I’ve read in a while. This is the first gender nonconforming girl I’ve really seen in a book (I’m sure there are others, but I haven’t encountered them) and I was really excited to read Pen’s story. It reminded me in some ways of what I’m trying to do with my own book Ugly, even though Pen is different in a lot of significant ways from my protagonist. Meet Cute is a collection of “meet cute” (the first meeting of a couple who will be starring in a romance) stories by some big names in YA contemporary and romance right now. By their very nature, some of these feel a little incomplete—because these are the stories of the meet only, not the rest of the romance. There are fourteen of them and definitely some are better than others, in my view.

Meet Cute is a collection of “meet cute” (the first meeting of a couple who will be starring in a romance) stories by some big names in YA contemporary and romance right now. By their very nature, some of these feel a little incomplete—because these are the stories of the meet only, not the rest of the romance. There are fourteen of them and definitely some are better than others, in my view. This is really a remarkable and very powerful book. First off, it’s a very engaging and exciting story with some action. You’ve got the Civil War setting and you’ve got zombies. I’m pretty sure that Civil War era isn’t a common setting in YA historical fiction, so that’s a nice thing right there. But Ireland has really twisted that setting with her introduction of zombies, or shamblers as they call them in the book (which is, by the way, an awesome term).

This is really a remarkable and very powerful book. First off, it’s a very engaging and exciting story with some action. You’ve got the Civil War setting and you’ve got zombies. I’m pretty sure that Civil War era isn’t a common setting in YA historical fiction, so that’s a nice thing right there. But Ireland has really twisted that setting with her introduction of zombies, or shamblers as they call them in the book (which is, by the way, an awesome term). There’s a lot of hype surrounding this book (for instance, I saw Entertainment Weekly called Adeyemi the next J. K. Rowling). Hype can be both good and bad. It had a lot to live up to, but I was still excited to read it, even though it’s way longer than my normal reads.

There’s a lot of hype surrounding this book (for instance, I saw Entertainment Weekly called Adeyemi the next J. K. Rowling). Hype can be both good and bad. It had a lot to live up to, but I was still excited to read it, even though it’s way longer than my normal reads. Niven’s other YA book, All the Bright Places, is probably going to remain one of my favorite YA novels of all time. So Holding Up the Universe had a lot to live up to, for me.

Niven’s other YA book, All the Bright Places, is probably going to remain one of my favorite YA novels of all time. So Holding Up the Universe had a lot to live up to, for me. This is a remarkable book that lives up to the hype surrounding it. Most of you will probably already know of this book, so you’ll know it’s about a black girl whose unarmed, black male friend gets shot by a white cop in front of her. Obviously a topical subject, but the book really delivers a great fiction experience all while introducing readers to a world they probably don’t know at all, as well as an inside perspective on what black people regularly face. I love reading books set in places or cultures I have little to no exposure to, even though it’s uncomfortable at times, and that was all true for this book.

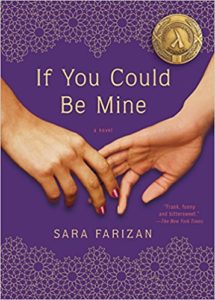

This is a remarkable book that lives up to the hype surrounding it. Most of you will probably already know of this book, so you’ll know it’s about a black girl whose unarmed, black male friend gets shot by a white cop in front of her. Obviously a topical subject, but the book really delivers a great fiction experience all while introducing readers to a world they probably don’t know at all, as well as an inside perspective on what black people regularly face. I love reading books set in places or cultures I have little to no exposure to, even though it’s uncomfortable at times, and that was all true for this book. If You Could Be Mine is set in modern-day Iran, which is definitely a setting I’m not very familiar with, so I was excited to read it. It’s narrated by Sahar, a seventeen-year-old lesbian, which is not okay in Iran. In fact, it’s illegal and the penalty can be as dramatic as death. The immediate problem for Sahar is that she has been in love with her friend Nasrin for as long as she can remember, and Nasrin loves her back. Of course, they spend a lot of time alone and this allows them to make out uninterrupted, so everything is fine.

If You Could Be Mine is set in modern-day Iran, which is definitely a setting I’m not very familiar with, so I was excited to read it. It’s narrated by Sahar, a seventeen-year-old lesbian, which is not okay in Iran. In fact, it’s illegal and the penalty can be as dramatic as death. The immediate problem for Sahar is that she has been in love with her friend Nasrin for as long as she can remember, and Nasrin loves her back. Of course, they spend a lot of time alone and this allows them to make out uninterrupted, so everything is fine.