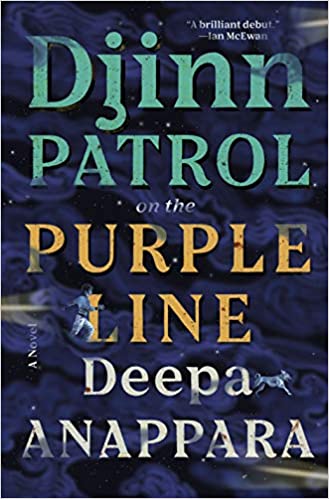

I rarely review books here that aren’t YA, but I enjoyed this one and think some of you might, as well. This is a rare suspense novel set in India (at least it’s rare to me—when I think of suspense, it’s almost always with white characters).

I rarely review books here that aren’t YA, but I enjoyed this one and think some of you might, as well. This is a rare suspense novel set in India (at least it’s rare to me—when I think of suspense, it’s almost always with white characters).

Jai is a nine-year-old Hindu boy in what I think is a slum in a fictional Indian city. He has two good friends, Pari, who’s a girl and smarter than him (though he’d be loathe to admit it), and Faiz, a Muslim boy. Jai is a little obsessed with crime shows and thinks he’d make a great detective. So when a classmate of his goes missing, he takes it upon himself to find out what happened, enlisting Pari and Faiz as his assistants. He feels this is necessary, since the police came, bribed the missing boy’s mom for her one valuable item, a gold chain given to her by her employer, and left promising to do exactly nothing. Bringing the police in is a source of tension for the entire slum, because they are always threatening to raze it, which would obviously make a huge number of people homeless. The three kids start investigating, but before they make much progress, another boy goes missing. Then a girl. As things escalate, so does their investigation, at least until it seems positively impossible.

One of the things I loved the most about the book was the authentic feel of a culture far removed from my every day life. Anappara has lots of details about living in the slum, because it’s all told through the perspective of someone who knows nothing but that (even if he thinks otherwise). There’s even a glossary in the back for all the Indian terms used for things like foods and slang, even though you can generally tell from the context what things are (I mean, not necessarily exactly, but you get the gist). But this really added to the flavor of the book. In general, Jai's voice is very colloquial, with statements like, “I like headstands a lot more than the huff-puff exercises…” so it makes complete sense that he’d be throwing in Indian terms.

Jai is a very annoying little brother to his twelve-year-old sister, even though he thinks she’s the annoying one. It’s interesting to see his perspective in this and everything else, because the reader can see clearly how wrong he is about things, which is often funny. For example, he’s trying to be the boss of his friends, and be the official detective:

“How come you get to be the detective?” Pari asks.

“That’s very true,” Faiz says. “Why can’t you be my assistant?”

“Arrey, what do you know about being a detective? You don’t even watch Police Patrol.”

“I know about Sherlock and Watson,” Pari says. “You two haven’t even heard of them.”

“What-son?” Faiz asks. “Is that also a Bengali name?”

I really enjoyed this book and recommend it for anyone looking for a different kind of suspense novel that also touches on social issues in India.

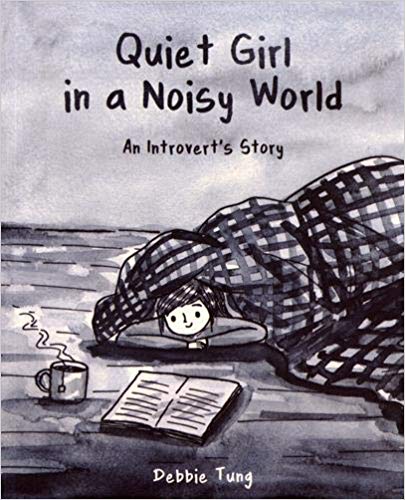

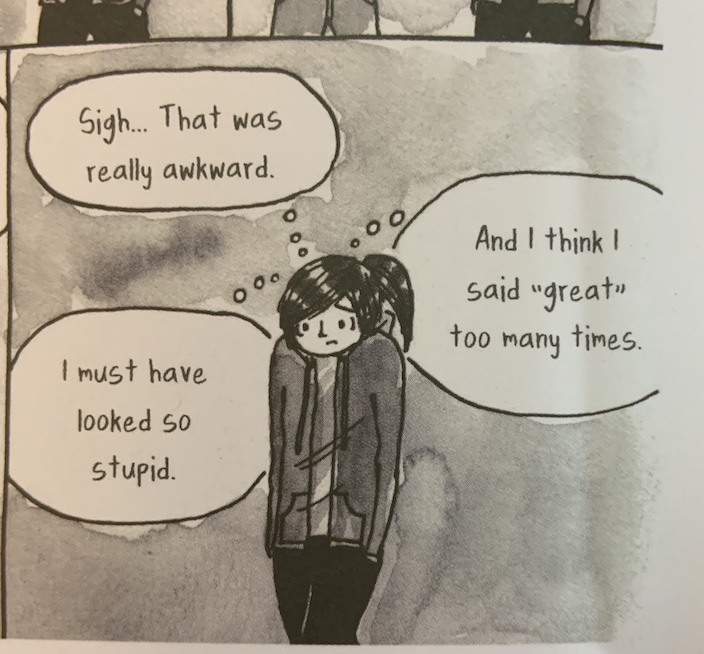

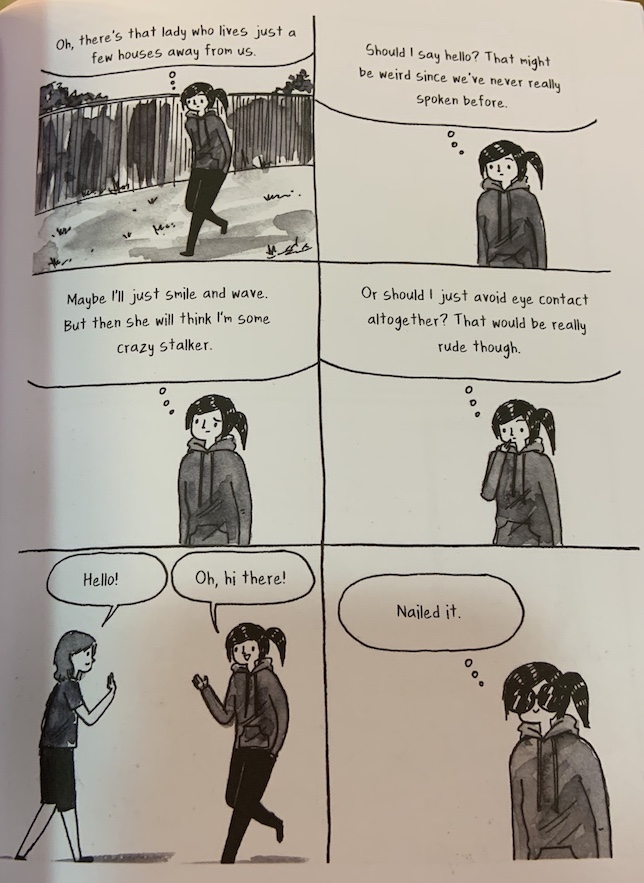

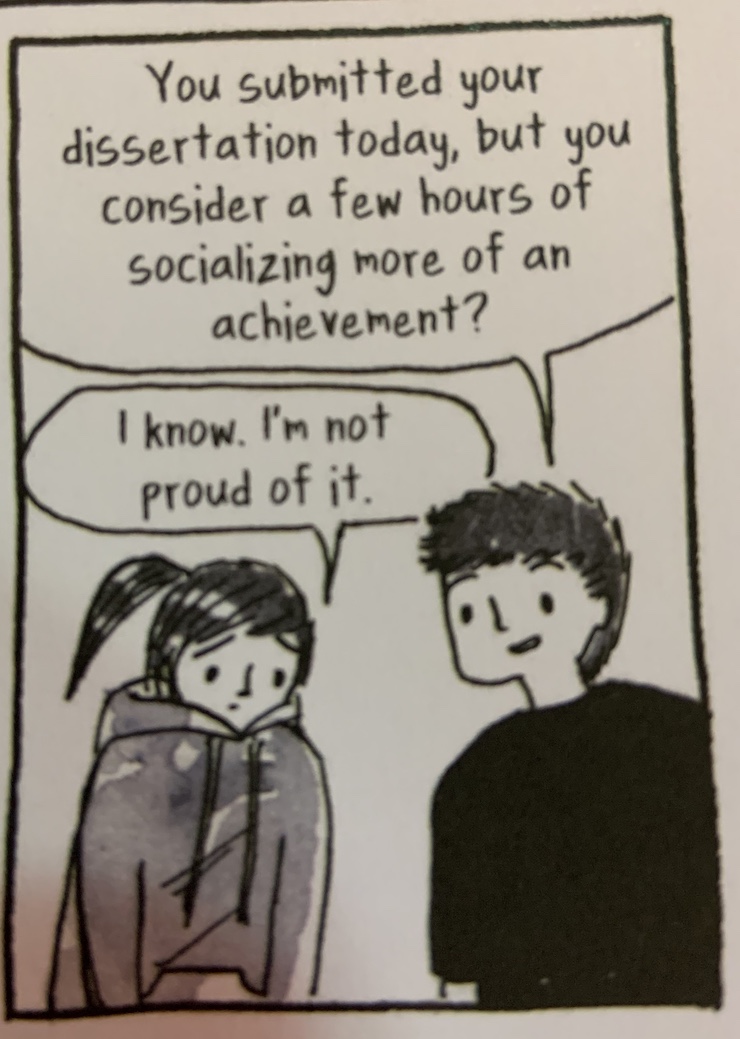

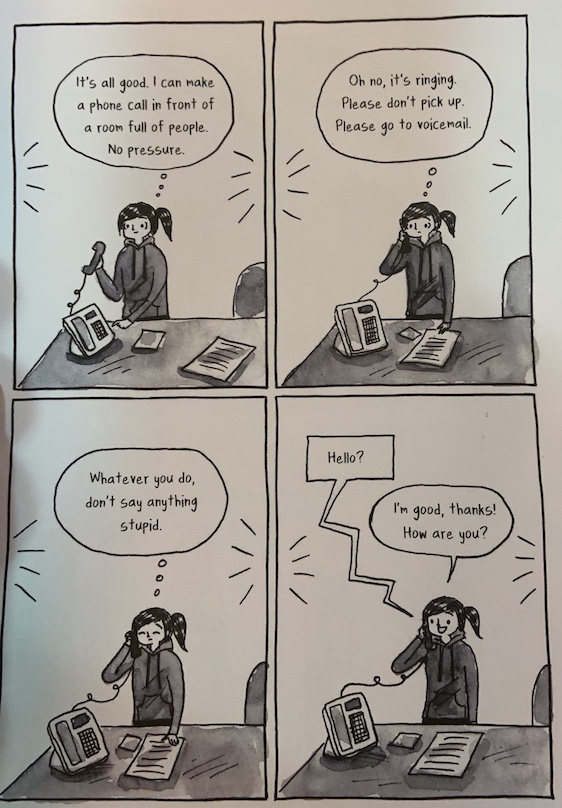

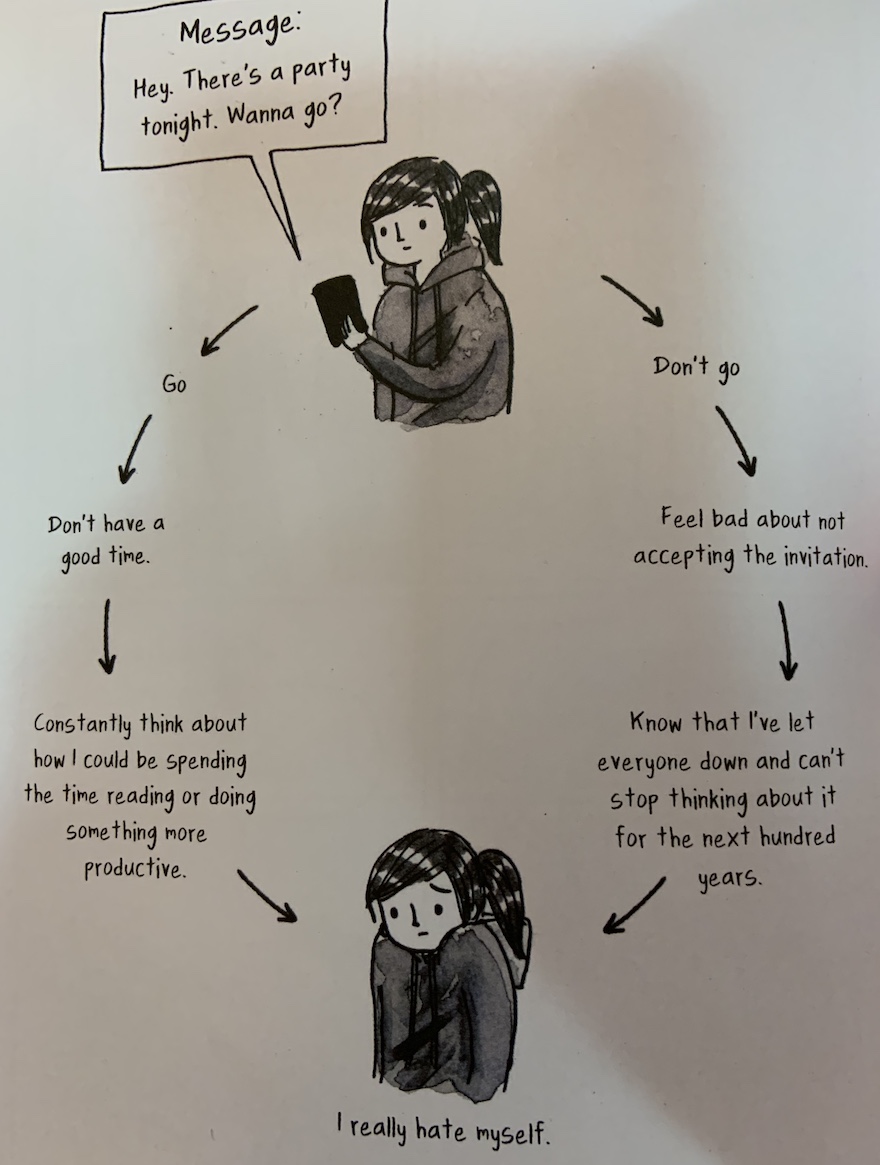

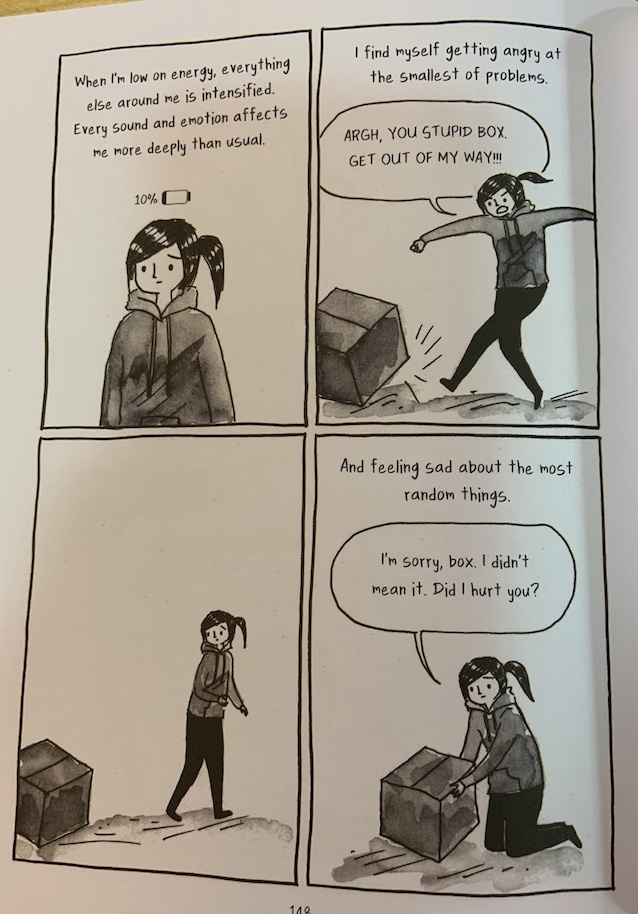

I’ve just discovered a new gem in this author/artist. There were moments I was reading this when I thought Tung must have been channeling my thoughts word-for-word. Quiet Girl in a Noisy World: An Introvert’s Story is a memoir chronicling Tung’s life from late grad school at the University of Birmingham in England through her first real job. She reflects some on her childhood and basically shows how she came to realize that being shy and very introverted is okay, not something to be ashamed of. Her art style is subdued in black, white, and gray watercolors and I really liked it.

I’ve just discovered a new gem in this author/artist. There were moments I was reading this when I thought Tung must have been channeling my thoughts word-for-word. Quiet Girl in a Noisy World: An Introvert’s Story is a memoir chronicling Tung’s life from late grad school at the University of Birmingham in England through her first real job. She reflects some on her childhood and basically shows how she came to realize that being shy and very introverted is okay, not something to be ashamed of. Her art style is subdued in black, white, and gray watercolors and I really liked it.

The good news is that by the end of the book, she has discovered and accepted her introversion, and no longer beats herself up over it.

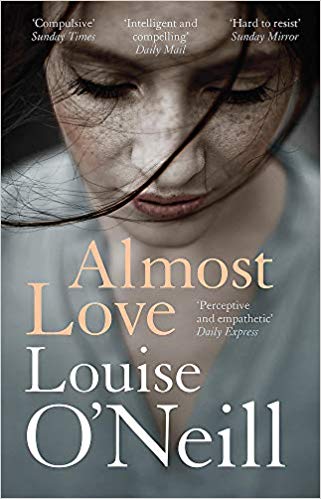

The good news is that by the end of the book, she has discovered and accepted her introversion, and no longer beats herself up over it. Although I generally review only YA books here, I’m making an exception this week. Not because it’s St. Patrick’s Day and this book is by an Irish writer, but because Louise O’Neill is one of my favorite authors even though she hasn’t written that many books—I’ve read her other three, all of which are YA (and all of which I’ve reviewed here). Almost Love is about a woman in her mid-twenties and almost has the feel of New Adult, but not quite.

Although I generally review only YA books here, I’m making an exception this week. Not because it’s St. Patrick’s Day and this book is by an Irish writer, but because Louise O’Neill is one of my favorite authors even though she hasn’t written that many books—I’ve read her other three, all of which are YA (and all of which I’ve reviewed here). Almost Love is about a woman in her mid-twenties and almost has the feel of New Adult, but not quite.