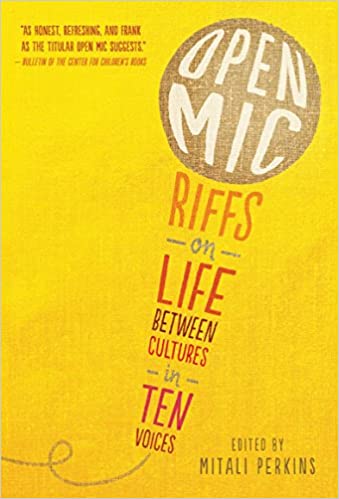

This slim volume of short stories/short memoirs by a variety of ethnically diverse authors is pretty entertaining. Most of the stories are by immigrants or children of immigrants (who have come to the US), with at least one is by a Black American (possibly more—I’m not certain). The goal of the book was to tell stories of people who exist in more than one culture, like so many people do, but with humor. I’ll say it definitely succeeds and I really enjoyed it, even though it wasn’t quite to the level of ROFL (I say that mostly so you don't have unreasonable expectations).

This slim volume of short stories/short memoirs by a variety of ethnically diverse authors is pretty entertaining. Most of the stories are by immigrants or children of immigrants (who have come to the US), with at least one is by a Black American (possibly more—I’m not certain). The goal of the book was to tell stories of people who exist in more than one culture, like so many people do, but with humor. I’ll say it definitely succeeds and I really enjoyed it, even though it wasn’t quite to the level of ROFL (I say that mostly so you don't have unreasonable expectations).

I have read and enjoyed books by a couple of the authors, Varian Johnson and Mitali Perkins, and I’ve heard of several of the others. So I’ll talk about their stories first, and then move on to the others.

“Three-Pointer”

Perkins’ story is (I’m assuming a true story) about a girl growing up as the youngest of three daughters of Indian immigrants living in a very white neighborhood. Perkins tells some funny (but also annoying) anecdotes like having to decline an offer from some hardcore Trekkies to play the brown girl in their reenactment of Star Trek episodes. But mostly she talks about liking boys along with her older sisters, and about her first secret date with a boy she’d had a crush on for a long time. Trying to learn about boys and all the relevant info in a deeply conservative household leads to a lot of funny beliefs and clarifications from her sisters.

“Like Me”

Johnson’s story is apparently fiction, about a Black boy at a very white, very small boarding school. Two new girls start at the school, and because they are Black twins, everyone expects the boy to immediately befriend them, but he hangs back. When his friends first talk about them with his friends, there’s an awkward conversation where they try to describe them without mentioning race and then make assumptions about how they’d be good at volleyball. Eventually they befriend each other, but the story isn’t really about that. It’s more about skirting two worlds. There were a couple of particularly funny parts in the story. The first is when the character is considering approaching the twins:

I mean, I could speak to them, but what am I supposed to say? Hello, my Negro friends. Welcome to Hobbs Academy, which is whiter than rice and eggshells and vanilla-flavored milk.

It cracked me up because it so highlights the absurdity of the expectation that everyone in a particular minority grouping would want to be friends. Except, also, it isn’t totally absurd that they'd want to at least know each other. Which is it’s a two-worlds thing, I suppose. The next one is more of a conceptual thing that’s funny, but Johnson totally captures how white Americans' “diversity” is “interesting” (and absurd) while non-white people’s ethnicity is generally considered more fundamental and consequential. He’s thinking about his friends:

Technically Rebecca is “one-eighth German, three-eighths Sephardic-Jewish, and one-half Irish.” And Evan has enough Muskogee blood running through him to be a member of the Creek Nation. Still, I didn’t see anyone looking at them when we talked about the Holocaust or the Trail of Tears last year in World History. But let anyone mention Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Will Smith or even the slightly black-looking dude who trims Principal Greer’s prized rosebushes, and suddenly I’m the center of attention.

It got bad during Black History Month.

I own February at Hobbs.

“Becoming Henry Lee”

The first story in the collection is this one by David Woo. It's about an eighth-grade boy with Chinese immigrant parents trying to convince everyone he’s white and being frustrated that all the stereotypical assumptions about him—being good at math and martial arts—were completely wrong. He deals with a lot of crap through eighth grade and into high school (much of which is presented as funny, but still disheartening) until he finally stops trying to be white and trying to be super-Asian, and just stumbling into something totally new that he discovers he loves. Now he has a way to define himself by something he chooses to do, not some happenstance of genetics.

“Why I Won’t Be Watching the Last Airbender Movie"

The next piece is also by an Asian-American author, Gene Yuen Lang. It’s a comic describing his frustration with the casting of the Last Airbender movie. The film was based on a cartoon that celebrated Asian-ness in a fictional Asian-inspired world (he says it showed “a deep respect for and knowledge of Asian cultures”), but all the major characters in the movie were filled by white actors. Lang publishes a call to boycott the movie, especially during release week, and ends up getting another great comics job out of it, all because he braved public scrutiny to stand up for something he believed in.

“Talent Show”

This one is by Cherry Cheva and is about a couple kids auditioning for a high school talent show. She’s stereotypically Asian—petite, cute, relatively quiet at first—but she’s there to do stand-up comedy. And it’s the white guy in the room holding the violin. They have an only-awkward-at-first conversation joking about stereotypes, and by the end they’re friends, even if their auditions don’t go as planned.

“Voilà!”

Debbie Rigaud's story is more sweet than funny, but I still liked it. It’s about a high school girl taking her beloved Haitian great aunt to the doctor. Some classmates doing volunteer work bring a couple of patients in and at first the girl is embarrassed, but eventually her obnoxious but well-meaning classmate suggests she could volunteer as a translator for some of the patients, and she sees clearly that her differentness doesn’t have to only be a burden.

“Confessions of a Black Geek”

This one by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich is about a group of confident, high-achieving (academically) Black high schoolers in the 80s. They assumed they were regarded as equals of their similarly high-achieving white peers. But a cartoon showing Black kids speaking “Ebonics” published in the school paper caused an uproar and it turned into a mess where they ended up getting called “reverse racists.” And this sort of opened the floodgates for all the microaggressions (and more overt stuff) they’d happily ignored for years.

And then comes the main character’s meeting with the guidance counselor, who tells her her intended schools are a “reach,” despite her academic and extracurricular record (which would have been more than sufficient for white students for this particular counselor). And then when she did get accepted to all these reach schools, everyone attributed it to affirmative action. She knew she’d earned it, but it was still heartbreaking to find out what so many people really think when they don't get what they want.

“Under Berlin” and "Lexicon"

The next piece is “Under Berlin” by G. Neri, and I’m going to admit that I didn’t read it because it was a long poem, and I simply cannot do poetry. For the same reason, I also skipped the last piece, “Lexicon” by Naomi Shihab Nye. I feel kind of bad about this, but trying to read poetry literally makes me feel anxious and/or agitated. I have no idea why.

“Brotherly Love”

The last story is by Francisco X. Stork and it’s about a boy growing up with a very traditional father from Mexico (I assumed? Definitely Spanish-speaking) and an older brother and sister. Their father was always going on about how “real men” behave and the main character engineers an opportunity to speak to his sister when no one else is around, because he’s worried that his brother is doing all these things that make him seem like he isn’t a real man. It’s a funny and ultimately sweet conversation when the character comes to realize what his sister has known all along—that it’s the main character who isn’t the “real man” and his brother has just been looking out for him.

Conclusion

So this was quite a long review for a book that is only 129 pages, but I wanted to talk about each story. Together, they add up to a nice exploration of living in two different worlds, culturally, linguistically, or however. The characters range in ages (eighth grade to graduating seniors), but this feels more lower-YA to me, as it stays fairly light in tone, even when dealing with troubling things.